Thanks to everyone who participated in our recent survey on job prep! We received some great feedback and we’re excited to share the results below.

(By the way, if you haven’t seen our latest survey on geographical preferences, check it out here!)

We opened our job prep survey to PhD grads and current PhD students, and we had comparable representation from each group (60% grads, 40% students). Respondents’ graduation years ranged from 1988 to 2015, with most completing their degrees in 2000 or later. About half of our respondents came from an English/Cultural Studies background; History and Classics/Religious Studies were also represented, as were a number of other disciplines.

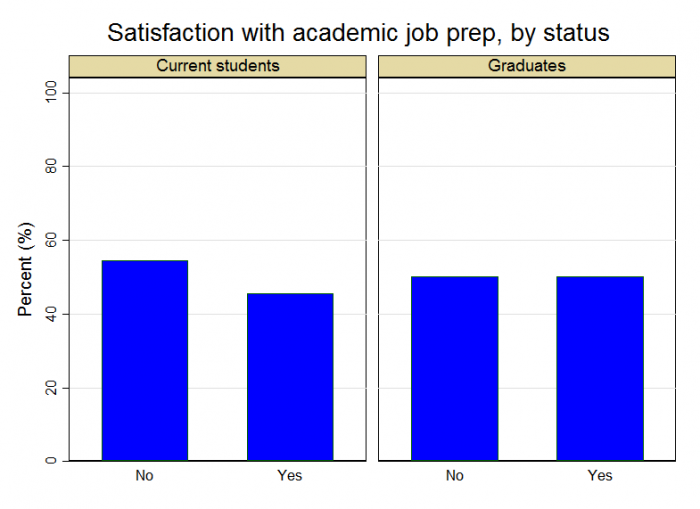

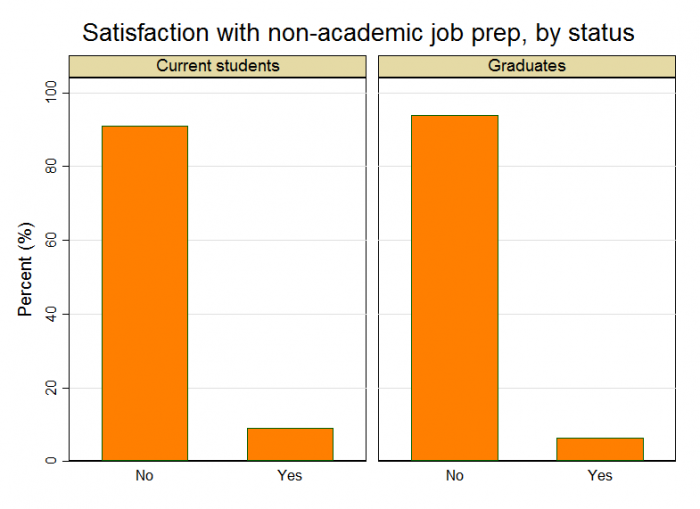

The plots below illustrate job prep satisfaction by respondent status (grads vs. current students). Overall, nearly half of our respondents were satisfied with the extent to which their departments prepared them for academic careers, but there was a high degree of dissatisfaction when it came to non-academic job prep. A small percentage of our respondents (7%) were satisfied with both academic and non-academic prep, but over half were dissatisfied with both. Satisfaction patterns were quite similar between grads and current students.

A few recurring themes emerged in the “Comments” section of the survey: first, respondents reported that many departments did not (or do not currently) have a formal job prep mechanism in place, particularly for non-academic careers. Second, while a number of respondents discussed departmental professionalization initiatives ranging from single day workshops to semester-long courses, the general consensus was that the programs/resources that are currently offered are not well-constructed or well-executed. Finally, although many respondents found faculty members generally unprepared to offer concrete guidance to students entering the job market, some of our respondents noted that strong one-on-one relationships with their supervisors, advisors, and/or committee members were valuable and very helpful with respect to career preparation.

The stigma of non-academic trajectories also featured prominently in our survey – specifically, departmental perceptions of non-academic work as “failure”. However, our survey suggests that the skills derived from a PhD are indeed transferrable to a non-academic context (likely unsurprising to our readers!). A few of our respondents wrote about their own transitions to the non-academic sphere and, while these transitions were generally difficult to navigate, they reported a high level of personal/professional fulfillment. Some also noted a favorable departmental shift in attitudes toward non-academic paths.

Our respondents may not be representative of all PhD grads and students in Canada (people who choose to take surveys tend to differ from those who don’t in important ways), but our results suggest that job preparation at the departmental level may be insufficient, especially for students considering non-academic paths. Refining/expanding existing departmental initiatives based on student/alumni feedback and allocating additional resources (for example, hiring versatile and knowledgeable job placement officers) could help to bridge this gap.

Does this align with your own experience? Feel free to leave a comment in the space below.

Thanks to everyone who participated in our recent survey on job prep! We received some great feedback and we’re excited to share the results below.

(By the way, if you haven’t seen our latest survey on geographical preferences, check it out here!)

We opened our job prep survey to PhD grads and current PhD students, and we had comparable representation from each group (60% grads, 40% students). Respondents’ graduation years ranged from 1988 to 2015, with most completing their degrees in 2000 or later. About half of our respondents came from an English/Cultural Studies background; History and Classics/Religious Studies were also represented, as were a number of other disciplines.

The plots below illustrate job prep satisfaction by respondent status (grads vs. current students). Overall, nearly half of our respondents were satisfied with the extent to which their departments prepared them for academic careers, but there was a high degree of dissatisfaction when it came to non-academic job prep. A small percentage of our respondents (7%) were satisfied with both academic and non-academic prep, but over half were dissatisfied with both. Satisfaction patterns were quite similar between grads and current students.

A few recurring themes emerged in the “Comments” section of the survey: first, respondents reported that many departments did not (or do not currently) have a formal job prep mechanism in place, particularly for non-academic careers. Second, while a number of respondents discussed departmental professionalization initiatives ranging from single day workshops to semester-long courses, the general consensus was that the programs/resources that are currently offered are not well-constructed or well-executed. Finally, although many respondents found faculty members generally unprepared to offer concrete guidance to students entering the job market, some of our respondents noted that strong one-on-one relationships with their supervisors, advisors, and/or committee members were valuable and very helpful with respect to career preparation.

The stigma of non-academic trajectories also featured prominently in our survey – specifically, departmental perceptions of non-academic work as “failure”. However, our survey suggests that the skills derived from a PhD are indeed transferrable to a non-academic context (likely unsurprising to our readers!). A few of our respondents wrote about their own transitions to the non-academic sphere and, while these transitions were generally difficult to navigate, they reported a high level of personal/professional fulfillment. Some also noted a favorable departmental shift in attitudes toward non-academic paths.

Our respondents may not be representative of all PhD grads and students in Canada (people who choose to take surveys tend to differ from those who don’t in important ways), but our results suggest that job preparation at the departmental level may be insufficient, especially for students considering non-academic paths. Refining/expanding existing departmental initiatives based on student/alumni feedback and allocating additional resources (for example, hiring versatile and knowledgeable job placement officers) could help to bridge this gap.

Does this align with your own experience? Feel free to leave a comment in the space below.

Discussion

Could you tell me more about the difference between those who choose to take surveys and those who don’t? I think this will be important for TRaCE going forward.

Great question, and something that comes up a LOT in statistics/study design. In general, there could be a number of important differences between respondents and non-respondents – for example, respondents may be more dissatisfied and/or more willing to talk openly about their experiences, whereas non-respondents might be more ambivalent about their experiences or simply uncomfortable engaging with online surveys. Unfortunately we’ll never know, as they didn’t respond! In the present scenario, if grads with positive job prep experiences were less likely to participate in our survey, we might be overestimating job prep dissatisfaction. This unbalanced “self-selection” phenomenon often yields a sample that is not representative of the underlying population, or the group in which we’re really interested (in our case, PhD grads from Canadian institutions), and this can produce biased estimates. The best way to avoid this bias would be to draw a random sample – this helps ensure that the overall distribution of participants’ characteristics is (on average) similar to the underlying population. Otherwise, we need to be conscious that our results might not be generalizable.

Great post! Even noting the self-selection of people who respond to surveys, this reflects a lot of the points that have been coming up in the narratives – I’m looking forward to seeing comparisons to the Stage 2 data when it’s coded and we can connect more of these strings.