Our dataset contains three progressively specific levels of employment data: broad job categories/sectors (higher education, for-profit, government, etc.), occupation types (tenure track, non-tenure track, instructor, counselor, etc.), and individuals’ actual job titles. We previously summarized trends in employment sectors by gender, department, and year of completion. In this post, we’ll begin to take a closer look at occupation types.

A few important caveats:

1) Relying solely on publicly-available employment information (as we did), it is often easier to identify a person’s general employment sector than their job type: our coders were able to capture job sector information for 80% of our sample, but more precise information on job type was only retrieved for 63%. Individuals with missing data are excluded from these early-stage analyses.

2) Given the data collection approach, there is a very real possibility of misclassification; this is compounded by the fact that many grads have more than one job. We assessed these on a case-by-case basis to determine which listed position would (likely) be a grad’s primary occupation, but we can’t be sure we’re correct. There is also some overlap between job types, as conceptualized here – for example, our “director” category is extremely diverse and spans various other categories. In short, it’s important to acknowledge the inherent subjectivity in our process, particularly with respect to this variable.

3) As this is the category in our dataset with the most uncertainty, our analyses and results should be considered exploratory/preliminary.

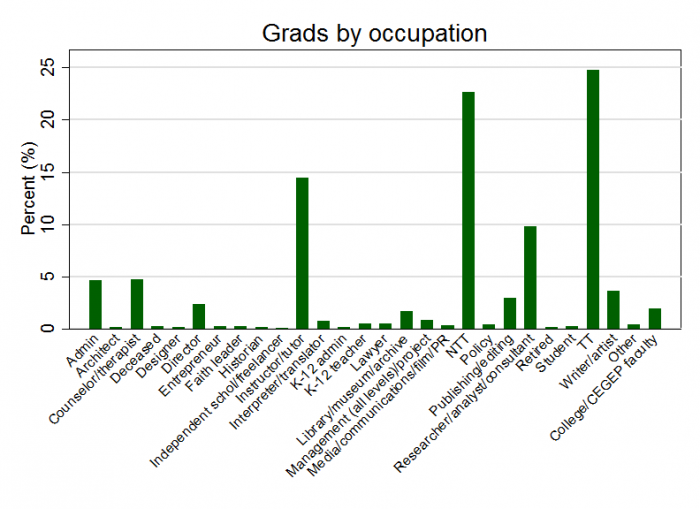

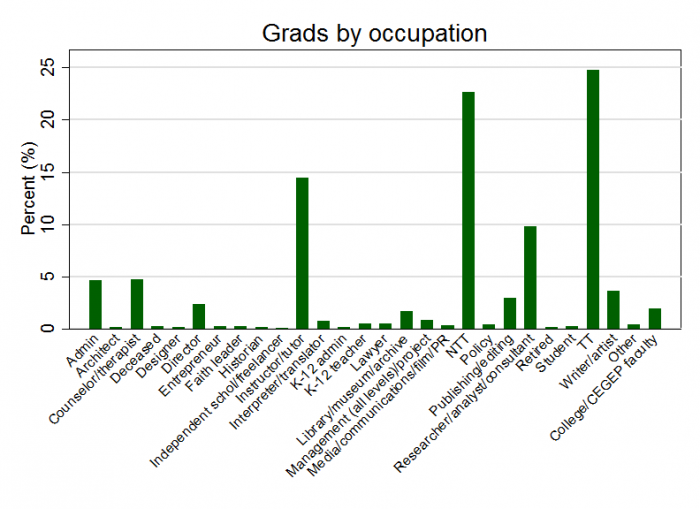

We illustrate the overall distribution/frequency of our sample’s various job types below. While there is an impressively diverse range of occupations, the sample is somewhat dominated by individuals with tenured/tenure-track (TT) and non-tenure track (NTT) positions. We also find a high concentration of instructors/tutors and researchers/analysts/consultants (we grouped these occupations together for reporting purposes).

In accordance with our initial report on employment sectors, the majority of grads for whom granular occupational information is available are employed in higher ed. Looking within this broader category, we find a diverse array of employment types: about two-thirds of our higher ed grads are classified as TT or NTT, but our dataset also contains university-level librarians, administrators, directors, researchers, students, college/CEGEP faculty, and more.

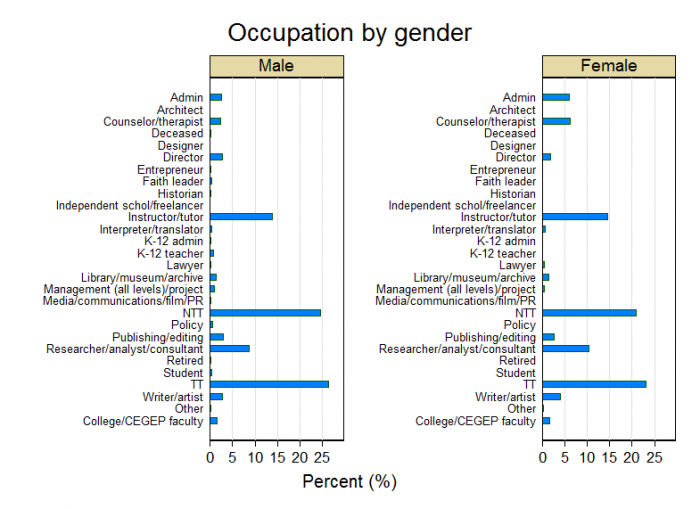

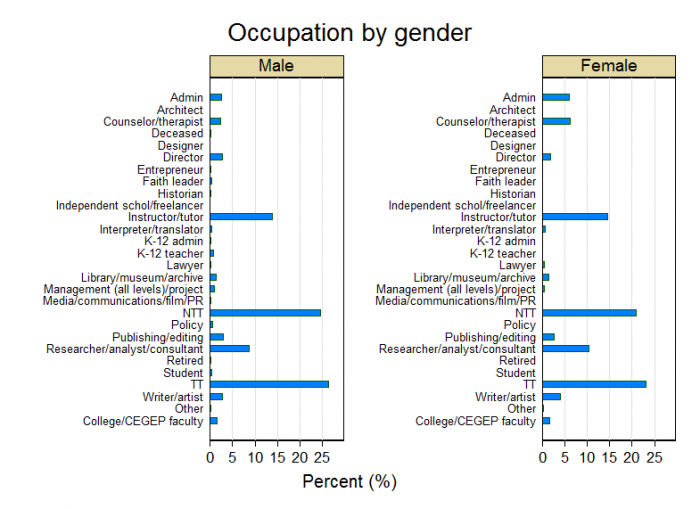

Gender-stratified employment distributions look relatively similar in our sample. However, the plots below suggest a few potential imbalances: for instance, it appears that a greater percentage of women work as administrators and counselors, and a greater percentage of men work in TT/NTT positions.

We’ll take a closer look at patterns by gender next time – check back soon!

Our dataset contains three progressively specific levels of employment data: broad job categories/sectors (higher education, for-profit, government, etc.), occupation types (tenure track, non-tenure track, instructor, counselor, etc.), and individuals’ actual job titles. We previously summarized trends in employment sectors by gender, department, and year of completion. In this post, we’ll begin to take a closer look at occupation types.

A few important caveats:

1) Relying solely on publicly-available employment information (as we did), it is often easier to identify a person’s general employment sector than their job type: our coders were able to capture job sector information for 80% of our sample, but more precise information on job type was only retrieved for 63%. Individuals with missing data are excluded from these early-stage analyses.

2) Given the data collection approach, there is a very real possibility of misclassification; this is compounded by the fact that many grads have more than one job. We assessed these on a case-by-case basis to determine which listed position would (likely) be a grad’s primary occupation, but we can’t be sure we’re correct. There is also some overlap between job types, as conceptualized here – for example, our “director” category is extremely diverse and spans various other categories. In short, it’s important to acknowledge the inherent subjectivity in our process, particularly with respect to this variable.

3) As this is the category in our dataset with the most uncertainty, our analyses and results should be considered exploratory/preliminary.

We illustrate the overall distribution/frequency of our sample’s various job types below. While there is an impressively diverse range of occupations, the sample is somewhat dominated by individuals with tenured/tenure-track (TT) and non-tenure track (NTT) positions. We also find a high concentration of instructors/tutors and researchers/analysts/consultants (we grouped these occupations together for reporting purposes).

In accordance with our initial report on employment sectors, the majority of grads for whom granular occupational information is available are employed in higher ed. Looking within this broader category, we find a diverse array of employment types: about two-thirds of our higher ed grads are classified as TT or NTT, but our dataset also contains university-level librarians, administrators, directors, researchers, students, college/CEGEP faculty, and more.

Gender-stratified employment distributions look relatively similar in our sample. However, the plots below suggest a few potential imbalances: for instance, it appears that a greater percentage of women work as administrators and counselors, and a greater percentage of men work in TT/NTT positions.

We’ll take a closer look at patterns by gender next time – check back soon!

Discussion